The bright turquoise glazes on Chinese ceramics is known in China as peacock green, due to its resemblance to peacock feathers. It is fired at a medium temperature and owes its colour to copper oxide in an alkaline glaze mix. The first turquoise alkaline glazes in China, are known from the Tang dynasty. They are found in small numbers, as a glaze on earthenware. The use of this colour, was further developed on the high fired stone wares of the Song dynasty. The colour was also used on ceramics in the Islamic world 9-13th centuries, where turquoise was widely used to decorated vessels and tiles. Turquoise glazes also had a long history in Egyptian culture, where it was used on ceramic burial figurines.

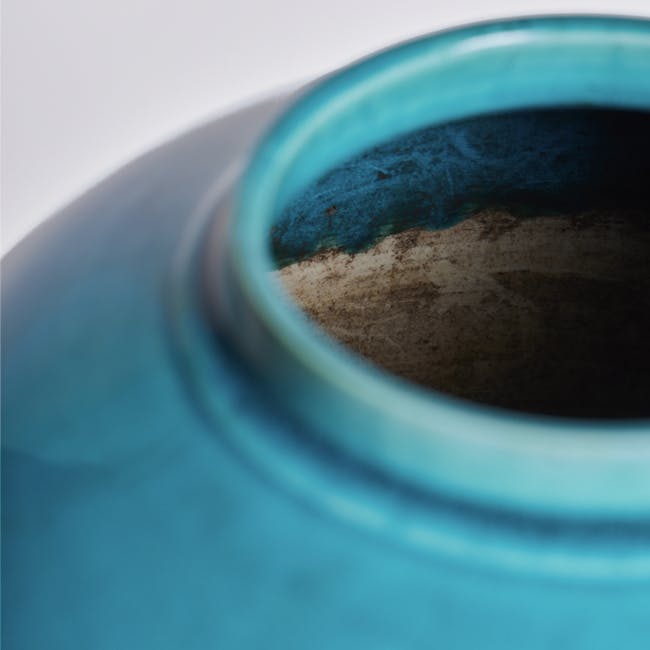

During the Yuan dynasty turquoise glazes began to be seen more frequently on Chinese ceramics. It was generally applied in a second firing, at a lower temperature, more like an enameling. From the Ming Dynasty onwards, it was applied to a pre-fired body or over a previously fired porcelain glaze. Turquoise was also used in combination with purple in what is known as the fahua palette. The colour became particularly popular in the 18th century, where the bright colour certainly appealed to the Emperors Kangxi & Qianlong. It would seem that the Kangxi potters at Jingdezhen were able to develop a turquoise glaze of greater depth and brilliance than had previously been achieved.

Turquoise enamel on biscuit porcelain also became very popular in Europe; where it started to gain its popularity in the West from the mid-18th century. Aristocratic and royal collectors in France, such as Marie Antoinette, greatly enjoyed the bright colour. We particularly find this type of porcelain in France, where it was often mounted with elaborate gilt bronze, also in combination with other pieces of porcelain. Collectors in England in the 19th and 20th century, such as Anthony de Rothschild, were also avid collectors of these monochrome wares.